The Smiths The Queen is Dead

-

Regular price

-

$48.00 SGD

-

Regular price

-

-

Sale price

-

$48.00 SGD

- Unit price

-

per

Couldn't load pickup availability

About

— The Analog Vault // Essential Listening —

The ironic poetry of Morrissey’s silver-tongued lyricism, paired with the complex melodies and arpeggios of Johnny Marr’s innovative guitar work, was indie rock’s loveliest musical marriage during the 1980s. Nowhere was that more evident than on The Smiths’ crowning achievement, The Queen Is Dead.

Released in 1986, the British band’s third album was a witty and gloomy outsider’s portrait of the UK under Margaret Thatcher’s severely conservative government and the monarchy’s classist rule. Morrissey has never been afraid to use his eloquent verses as a vehicle for lacerating self-reflection and social satire, but even by his lofty standards, the singer was in rare form here. Likewise, Marr’s compositions - aided adroitly by bassist Andy Rourke and drummer Mike Joyce - built the affecting sonic foundations and instrumental finesse of The Queen Is Dead, imbuing rich emotion into Morrissey’s wryness. — The Analog Vault

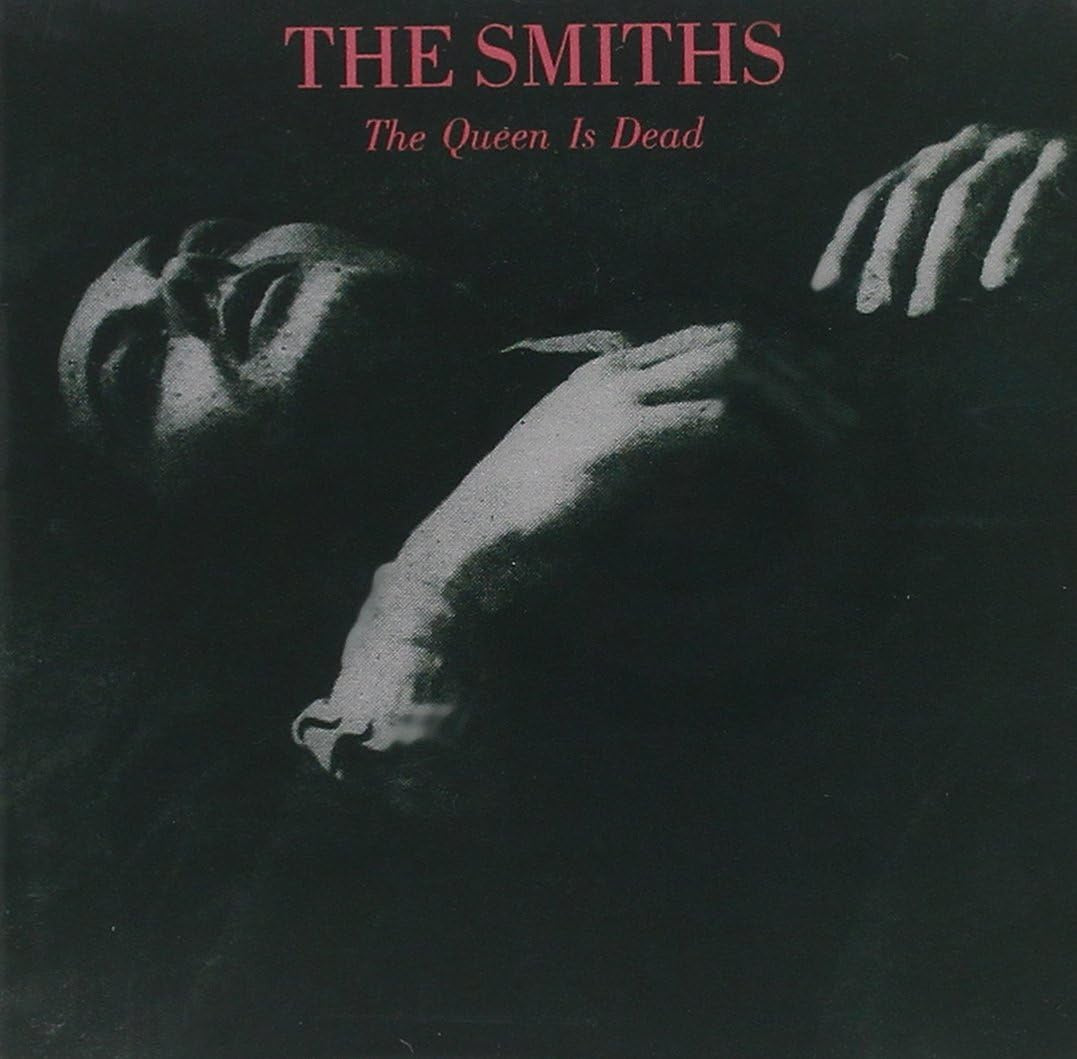

Title and cover : The album title is taken from American writer Hubert Selby Jr.'s 1964 novel, Last Exit to Brooklyn. The cover of The Queen Is Dead features a still of French actor Alain Delon from the 1964 film The Unvanquished. Delon granted permission for the image's use, though according to Morrissey's Autobiography, the actor mentioned that his parents were dismayed by the album's title. — (via Wiki)

Meat Is Murder may have been a holding pattern, but The Queen Is Dead is the Smiths' great leap forward, taking the band to new musical and lyrical heights. Opening with the storming title track, "The Queen Is Dead" is a harder-rocking record than anything the Smiths had attempted before, but that's only on a relative scale — although the backbeat is more pronounced, the group certainly doesn't rock in a conventional sense. Instead, Johnny Marr has created a dense web of guitars, alternating from the minor-key rush of "Bigmouth Strikes Again" and the faux rockabilly of "Vicar in a Tutu" to the bouncy acoustic pop of "Cemetry Gates" and "The Boy With the Thorn in His Side," as well as the lovely melancholy of "I Know It's Over" and "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out." And the rich musical bed provides Morrissey with the support for his finest set of lyrics. Shattering the myth that he is a self-pitying sap, Morrissey delivers a devastating set of clever, witty satires of British social mores, intellectualism, class, and even himself. He also crafts some of his finest, most affecting songs, particularly in the wistful "The Boy With the Thorn in His Side" and the epic "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out," two masterpieces that provide the foundation for a remarkable album. — (via AllMusic)

The Smiths’ 1986 masterpiece still stands as an enduring testament to England in the ’80s, the complex relationship between performer and fan, and the ecstasy of emptiness.

A complex allegory about arrested development on the individual and national level, “The Queen Is Dead” starts with a sample from The L-Shaped Room, one of those British black-and-white social realist films of the early ’60s that Morrissey adores. A middle-aged woman sings “Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty,” a First World War ditty of patriotic homesickness. Nostalgia folded within nostalgia, the sample—even if intended as bitterly ironic—shows Morrissey’s fatal attachment to the past. Like Rotten in “God Save the Queen,” Morrissey knows there’s no future in England’s dreaming; the country will never move forward until it abandons its imperial legacy of deluded exceptionalism. But the outlines of a future Brexit supporter are already becoming clear.

From Prince’s “Controversy” to Taylor Swift’s “Look What You Made Me Do,” it’s always perilous when pop stars start to address their own position as public figures. Where “The Queen Is Dead” is the sort of Big Statement a band makes when it acquires a sense of its own importance, “The Boy With the Thorn in His Side” is one of a group of full-blown meta-songs on the album. Morrissey appeals to the sympathy of his disciples by lamenting the far larger number of indifferent doubters out there: “How can they hear me say those words still they don’t believe me?” There is a hint of reveling in the martyr posture in “Bigmouth Strikes Again” too, what with its references to Joan of Arc going up in flames. It doubles as both a relationship song and a commentary on Morrissey as the controversialist forever getting in trouble for his caustic quips and sweeping statements.

“Frankly, Mr. Shankly” is petty as meta goes: At the time, nobody but a handful of music industry insiders could have known that it’s a mean-spirited swipe at Rough Trade’s Geoff Travis. What’s more interesting now is Morrissey’s admission of his insatiable lust for attention—“Fame fame fatal fame/It can play hideous tricks on the brain”—but nonetheless he’d “rather be famous than righteous or holy.” Couched in a jaunty music-hall bounce, the song also serves as a preemptive justification of the Smiths’ decision to break with Rough Trade for the biggest major label around, EMI.

The cleverest of the meta-pop Smiths songs of this period, though, can be found on this reissue’s second disc of B-sides and demos. Originally the flipside to “Boy With the Thorn,” “Rubber Ring” gets its name from the life-preservers you find on ships. Although his songs once saved their lives, Morrissey anticipates his fans abandoning him as they grow out of the maladjustment and amorous ineptitude in which he will remain perpetually trapped. The empty young lives will fill up with all the normal sorts of happiness, he predicts, and the Smiths records will be filed away and forgotten. “Do you love me like you used to?” Morrissey beseeches, as if he’s actually in a real romance with each and every one of his fans, acutely aware of the perversity and impossibility at work in pop’s psycho-dynamics of identification and projection.

Two other loose categories could be formed out of the songs on The Queen Is Dead: Beside the meta, there’s the merry and the melancholy. Despite the morbid (and misspelled) title, “Cemetry Gates” is sprightly and carefree. Even though they’re strolling among the gravestones quoting poetry at each other to show how intensely they feel the sorrow of mortality, the life-force is strong in these precocious youngsters. As so often with Morrissey, the frissons come with the tiny quirks of unusual word-choice or phrasing—the little jolt of the way he pronounces “plagiarize” with an incorrect hard “g,” for instance. Featuring the album’s second instance of cross-dressing, “Vicar in a Tutu” is a slight delight with just a casual twist of subversiveness in a passing reference to the priest’s kinky antics being “as natural as rain”: This freak is just as God made him. Almost cosmic in its insubstantiality, “Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others” seemed at the time an anticlimactic ending to such an Important Album. Now I think the understatement is just right, rather than the obvious curtain-closer, “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out”—the glide and glisten of Marr’s playing on “Some Girls” is that never-fading light.

And then there’s the life-and-death serious stuff. Both songs of unrequited love, “I Know It’s Over” and “There Is a Light” make a pair: The first spins majesty out of misery, the second transcends it with a sublime and nakedly religious vision of hope-in-vain as an end in itself. The writing in “I Know It’s Over” is a tour de force, from the opening image of the empty—sexless, loveless—bed as a grave, through the suicidal inversions of “The sea wants to take me/The knife wants to slit me,” onto the self-lacerations of “If you’re so funny, then why are you on your own tonight?” and finally the unexpected and amazing grace of “It’s so easy to hate/It takes strength to be gentle and kind.” Not a strong or sure singer by conventional standards, Morrissey gives his all-time greatest vocal performance, something ear-witness Johnny Marr described as “one of the highlights of my life.”

As for “There Is a Light”—if you don’t tear up at the chorus, you belong to a different species. The scenario involves another doomed affair, a love (and a life—Morrissey’s) that never really started. But here Morrissey hovers in an ecstatic suspension of yearning that becomes its own satisfaction, an emptiness that becomes a plenitude. The greatest of his many songs about not belonging anywhere or to anyone, it so very nearly tumbles into comedy (and there are those who’ve laughed) with the melodramatic excess of its image of the double-decker bus and the romantic entwining-in-death of the not-quite-lovers. But the trembling sincerity of “the pleasure, the privilege is mine” keeps it on the right side of the gravity/levity divide in the Smiths songbook. — (excerpts from Pitchfork)

↓

Label: Warner Music

Format: Vinyl, LP, Album, Reissue, Gatefold, 180g

Reissued: 2012 / Original: 1986

Genre: Rock, Pop

Style: Indie Rock, Indie Pop, Alternative Rock, Post-Punk, Male Vocals

File under: Indie Rock

⦿

Share

- Regular price

- $48.00 SGD

- Regular price

-

- Sale price

- $48.00 SGD

- Unit price

- per

Couldn't load pickup availability

About

— The Analog Vault // Essential Listening —

The ironic poetry of Morrissey’s silver-tongued lyricism, paired with the complex melodies and arpeggios of Johnny Marr’s innovative guitar work, was indie rock’s loveliest musical marriage during the 1980s. Nowhere was that more evident than on The Smiths’ crowning achievement, The Queen Is Dead.

Released in 1986, the British band’s third album was a witty and gloomy outsider’s portrait of the UK under Margaret Thatcher’s severely conservative government and the monarchy’s classist rule. Morrissey has never been afraid to use his eloquent verses as a vehicle for lacerating self-reflection and social satire, but even by his lofty standards, the singer was in rare form here. Likewise, Marr’s compositions - aided adroitly by bassist Andy Rourke and drummer Mike Joyce - built the affecting sonic foundations and instrumental finesse of The Queen Is Dead, imbuing rich emotion into Morrissey’s wryness. — The Analog Vault

Title and cover : The album title is taken from American writer Hubert Selby Jr.'s 1964 novel, Last Exit to Brooklyn. The cover of The Queen Is Dead features a still of French actor Alain Delon from the 1964 film The Unvanquished. Delon granted permission for the image's use, though according to Morrissey's Autobiography, the actor mentioned that his parents were dismayed by the album's title. — (via Wiki)

Meat Is Murder may have been a holding pattern, but The Queen Is Dead is the Smiths' great leap forward, taking the band to new musical and lyrical heights. Opening with the storming title track, "The Queen Is Dead" is a harder-rocking record than anything the Smiths had attempted before, but that's only on a relative scale — although the backbeat is more pronounced, the group certainly doesn't rock in a conventional sense. Instead, Johnny Marr has created a dense web of guitars, alternating from the minor-key rush of "Bigmouth Strikes Again" and the faux rockabilly of "Vicar in a Tutu" to the bouncy acoustic pop of "Cemetry Gates" and "The Boy With the Thorn in His Side," as well as the lovely melancholy of "I Know It's Over" and "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out." And the rich musical bed provides Morrissey with the support for his finest set of lyrics. Shattering the myth that he is a self-pitying sap, Morrissey delivers a devastating set of clever, witty satires of British social mores, intellectualism, class, and even himself. He also crafts some of his finest, most affecting songs, particularly in the wistful "The Boy With the Thorn in His Side" and the epic "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out," two masterpieces that provide the foundation for a remarkable album. — (via AllMusic)

The Smiths’ 1986 masterpiece still stands as an enduring testament to England in the ’80s, the complex relationship between performer and fan, and the ecstasy of emptiness.

A complex allegory about arrested development on the individual and national level, “The Queen Is Dead” starts with a sample from The L-Shaped Room, one of those British black-and-white social realist films of the early ’60s that Morrissey adores. A middle-aged woman sings “Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty,” a First World War ditty of patriotic homesickness. Nostalgia folded within nostalgia, the sample—even if intended as bitterly ironic—shows Morrissey’s fatal attachment to the past. Like Rotten in “God Save the Queen,” Morrissey knows there’s no future in England’s dreaming; the country will never move forward until it abandons its imperial legacy of deluded exceptionalism. But the outlines of a future Brexit supporter are already becoming clear.

From Prince’s “Controversy” to Taylor Swift’s “Look What You Made Me Do,” it’s always perilous when pop stars start to address their own position as public figures. Where “The Queen Is Dead” is the sort of Big Statement a band makes when it acquires a sense of its own importance, “The Boy With the Thorn in His Side” is one of a group of full-blown meta-songs on the album. Morrissey appeals to the sympathy of his disciples by lamenting the far larger number of indifferent doubters out there: “How can they hear me say those words still they don’t believe me?” There is a hint of reveling in the martyr posture in “Bigmouth Strikes Again” too, what with its references to Joan of Arc going up in flames. It doubles as both a relationship song and a commentary on Morrissey as the controversialist forever getting in trouble for his caustic quips and sweeping statements.

“Frankly, Mr. Shankly” is petty as meta goes: At the time, nobody but a handful of music industry insiders could have known that it’s a mean-spirited swipe at Rough Trade’s Geoff Travis. What’s more interesting now is Morrissey’s admission of his insatiable lust for attention—“Fame fame fatal fame/It can play hideous tricks on the brain”—but nonetheless he’d “rather be famous than righteous or holy.” Couched in a jaunty music-hall bounce, the song also serves as a preemptive justification of the Smiths’ decision to break with Rough Trade for the biggest major label around, EMI.

The cleverest of the meta-pop Smiths songs of this period, though, can be found on this reissue’s second disc of B-sides and demos. Originally the flipside to “Boy With the Thorn,” “Rubber Ring” gets its name from the life-preservers you find on ships. Although his songs once saved their lives, Morrissey anticipates his fans abandoning him as they grow out of the maladjustment and amorous ineptitude in which he will remain perpetually trapped. The empty young lives will fill up with all the normal sorts of happiness, he predicts, and the Smiths records will be filed away and forgotten. “Do you love me like you used to?” Morrissey beseeches, as if he’s actually in a real romance with each and every one of his fans, acutely aware of the perversity and impossibility at work in pop’s psycho-dynamics of identification and projection.

Two other loose categories could be formed out of the songs on The Queen Is Dead: Beside the meta, there’s the merry and the melancholy. Despite the morbid (and misspelled) title, “Cemetry Gates” is sprightly and carefree. Even though they’re strolling among the gravestones quoting poetry at each other to show how intensely they feel the sorrow of mortality, the life-force is strong in these precocious youngsters. As so often with Morrissey, the frissons come with the tiny quirks of unusual word-choice or phrasing—the little jolt of the way he pronounces “plagiarize” with an incorrect hard “g,” for instance. Featuring the album’s second instance of cross-dressing, “Vicar in a Tutu” is a slight delight with just a casual twist of subversiveness in a passing reference to the priest’s kinky antics being “as natural as rain”: This freak is just as God made him. Almost cosmic in its insubstantiality, “Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others” seemed at the time an anticlimactic ending to such an Important Album. Now I think the understatement is just right, rather than the obvious curtain-closer, “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out”—the glide and glisten of Marr’s playing on “Some Girls” is that never-fading light.

And then there’s the life-and-death serious stuff. Both songs of unrequited love, “I Know It’s Over” and “There Is a Light” make a pair: The first spins majesty out of misery, the second transcends it with a sublime and nakedly religious vision of hope-in-vain as an end in itself. The writing in “I Know It’s Over” is a tour de force, from the opening image of the empty—sexless, loveless—bed as a grave, through the suicidal inversions of “The sea wants to take me/The knife wants to slit me,” onto the self-lacerations of “If you’re so funny, then why are you on your own tonight?” and finally the unexpected and amazing grace of “It’s so easy to hate/It takes strength to be gentle and kind.” Not a strong or sure singer by conventional standards, Morrissey gives his all-time greatest vocal performance, something ear-witness Johnny Marr described as “one of the highlights of my life.”

As for “There Is a Light”—if you don’t tear up at the chorus, you belong to a different species. The scenario involves another doomed affair, a love (and a life—Morrissey’s) that never really started. But here Morrissey hovers in an ecstatic suspension of yearning that becomes its own satisfaction, an emptiness that becomes a plenitude. The greatest of his many songs about not belonging anywhere or to anyone, it so very nearly tumbles into comedy (and there are those who’ve laughed) with the melodramatic excess of its image of the double-decker bus and the romantic entwining-in-death of the not-quite-lovers. But the trembling sincerity of “the pleasure, the privilege is mine” keeps it on the right side of the gravity/levity divide in the Smiths songbook. — (excerpts from Pitchfork)

↓

Label: Warner Music

Format: Vinyl, LP, Album, Reissue, Gatefold, 180g

Reissued: 2012 / Original: 1986

Genre: Rock, Pop

Style: Indie Rock, Indie Pop, Alternative Rock, Post-Punk, Male Vocals

File under: Indie Rock

⦿

Share

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.